QUT is seeking to improve its outcomes for women in STEMM careers, with a strong focus on the research dimension.

An advocate for women in STEMM and a former CEO of the Australian Research Council, Vice-Chancellor Professor Margaret Sheil AO shares her vision and insights in a speech given at QUT’s 2018 International Women Day event.

I am delighted and honoured to be addressing you today, to celebrate International Women’s Day tomorrow.

This is my fourth week in the role of Vice-Chancellor and I have had a few speaking engagements already, but this is my first big speech. I could not have chosen a more opportune moment or a more appropriate topic for my first major address, in light of the focus I have given throughout my career to the question of gender equity in higher education and research, particularly in science.

In deference to time, I will skip over the experiences of my early career, only to mention that I faced all the usual systemic obstructions that women face, including the challenges of being a mother in a male-dominated workplace, and the unconscious – and not so unconscious – bias of a world that was still mostly run by and for greying white men, in my case in lab coats rather than suits or cardigans.

There was little allowance made for childcare; accomplishment was calculated solely in terms of raw track record; any attempt to explain career breaks was couched in a deficit model; and decisions were made by committees on which women were outnumbered, when they were there at all.

In other words, it was nothing that every woman of my age here wouldn’t know intimately from her own experience. In my case I succeeded in part because I was fortunate to have the three essential elements if you wanted to combine a family and career – namely, a good partner, a good boss, and most important of all, a truly wonderful Mother, who I know is looking down on me from somewhere with pride.

I was appointed CEO of the ARC in 2007 by Julie Bishop, who was then Minister for Education, Science and Training, as well as Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Women’s Issues. With a selection committee chaired by the then Education Secretary, Lisa Paul – a confluence that was important in ensuring there was no impediment to a qualified woman being offered the role – and I was up for the challenge.

My very first decision at the ARC was to reject the recommendation to appoint six male committee chairs and told them to come back with 3 women. That set the tone…

Not long after I was advised by a senior woman to leave the gender issue alone otherwise it would define my time at the ARC. She argued that, in any case, once you correct for level of appointment, it’s simply a pipeline problem that will fix itself over time.

So I wondered: if I didn’t address this, who would – the next bloke appointed to the role?

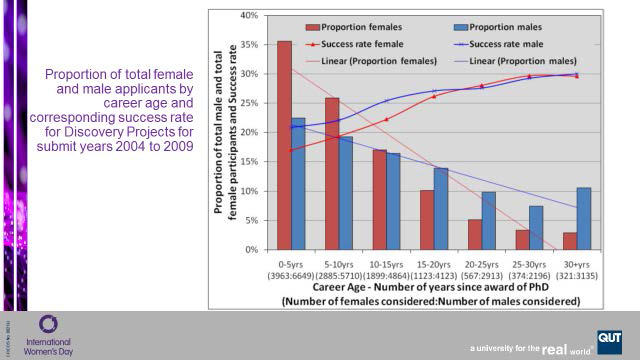

Being a scientist the first thing I did was look at the data. I am sorry this is a really busy slide but it is one of the more illuminating data analyses which illustrates a number of trends in participation in the research workforce based on ARC application data to the main scheme known as ARC Discovery.

Contrary to the advice I was given the problems were not just insufficient women at the top end – that was a problem I will come back to but the really startling evidence was at the early career stage, where the biggest differences in success rate emerge.

There was a problem with the pipeline, which was and still is more acute in science, and even more so in engineering and IT where the lines never cross.

But in the US where there had been more women in the system for longer, the pattern was the same.

So we got to work on addressing the language and the parameters around assessing research accomplishment, so that performance was regarded relative to opportunity – to actual time on the job, rather than against a race track that you couldn’t step off.

We introduced the DECRA scheme to reduce the effect of male patronage, since the problem with differential success rates was worse at the start of women’s careers.

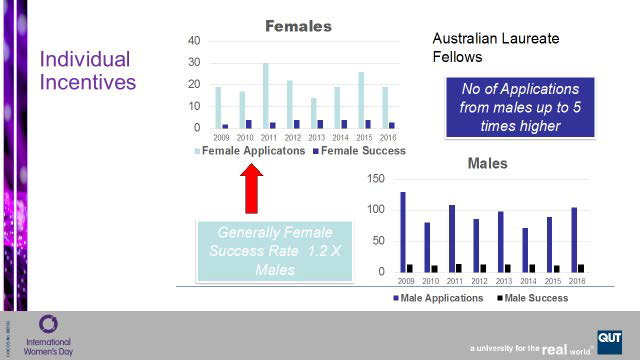

At the senior end of the career spectrum, there were equally startling trends in the Laureate scheme – while the women who applied were more successful per capita than the men, they were far outnumbered by male applicants:

After a series of meetings centred around a visit home by Australian Nobel Laureate Elizabeth Blackburn, we added two Laureate Fellowships for senior women, and furnished them with additional resources for mentoring and programs to advance the careers of talented women in their fields. In an early morning phone call another Science Minister, Kim Carr, made the canny suggestion to name these designated fellowships after distinguished (and deceased) Australian researchers, to prevent them being politicised or retracted.

Thus the Georgina Sweet and Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellowships were born, for outstanding women researchers in science and technology, and in the humanities and social sciences, respectively.

Recently the scheme was criticised by someone saying that we were asking women to do more – but in fact we designed this recognising that many successful women were actively supporting women already. Women such as the inspirational Queenslander Jenny Martin who used the profile of her 2009 Laureate to call out a number of issues, especially women presenters at scientific conferences. I was delighted to see her recognised with an AC, and to see Michelle Simmons, another ARC Laureate Fellow be made Australian of the Year on Australia Day earlier this year.

We achieved better outcomes with these awards, in terms of empowering creative individuals to do new and daring things to boost women’s careers, such as Nalini Joshi using her Georgina Sweet Fellowship to get the Science in Australia Gender Equity initiative going, in collaboration with some others including Tanya Munro.

But I am disappointed that the incentives in the Laureate here have not substantially shifted the numbers from 3-4 out of 15-17 each year, as you can see from the graph above.

So we need to do more at an institutional level, especially at mid-career to bring women through into the pool of applicants.

Which is a nice segue to QUT, where it won’t surprise you to hear I have taken an early and keen interest in the university’s gender equity position. I couldn’t have ignored it even if I’d wanted to: in my second week QUT was once again recognised as an Employer of Choice for Gender Equity by the federal Government’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency. It was a lovely welcome. This is testimony to years of dedication to principles of equality at QUT, to years of leadership by the many champions of positive change at this institution. We can all be proud of that recognition, and I thank and congratulate everyone at QUT who has helped to produce that result. QUT has been on this list since 2005, something only a handful of other Australian universities have achieved.

But I know that all responsible will agree – that you will all agree – that the work has only just begun. It is gratifying to do well in the eyes of others, of course, as it is to do well relative to the sector. But there’s a trap in those plaudits, and in performing above the line: doing well can feel a lot like doing well enough, when we all know there is a lot more to be done.

We need to measure our achievements not against other universities or against the regard of others, but against our expectations of ourselves, against our conception of fairness and justice and equity, against the standard we need to reach before we can say that gender truly holds no one back from access to opportunity, recognition and success.

So let’s have a look at how QUT is going, based on some hard data – the scientist again.

We compare reasonably well against the sector for women’s representation in senior staff, at a little over 40% overall.

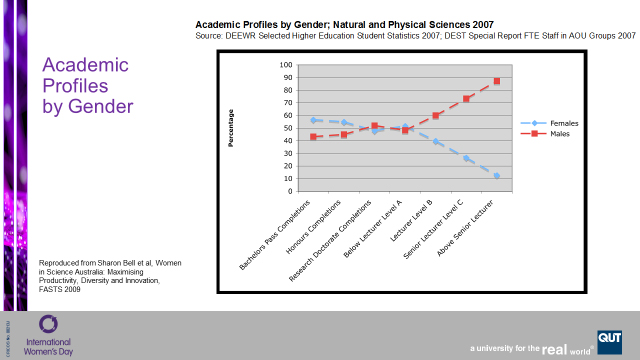

The professional cohort at senior level is strong, and has shown steady growth in the main. The academic cohort is less strong and mirrors the national pattern by level. At QUT, levels A, B and C come in around the 50% mark, dropping below 40% at D and below 36% at level E.

Even though workplace marginalisation happens to women right across the workforce; school pickup is the same time whether you’re an historian or a physicist. It is worth breaking down these figures a little further into the broad categories of STEMM and non-STEMM disciplines. You can see there are not only fewer women in the STEMM area, but that the drop is much steeper.

For science and engineering, this is your classic black diamond run, and the valley floor at the bottom is low altitude indeed – only one in five full professors across science and technology here is female.

In some disciplines it’s as low as one in ten.

Think for a moment what that dramatic collapse represents, what the sustained absence of senior women in these disciplines must mean for role-modelling, for mentoring, for the creation of a supportive environment and a nurturing disciplinary culture, for fostering talent and knowledge-creation. I venture that this is not only a problem for women, but also for men coming through, who will be inducted into a distorted idea of a scientific workplace that is radically out of step with the world outside the lab. You can see now why I think we need to put in additional urgent effort into women in science and engineering.

Let me be clear: we do not have a particular problem in this respect at QUT. This situation is reflective of the national, and even international, picture. The issues at play seem to be the same as well, as do the approaches that will overcome them.

QUT has articulated these over recent times, and with the SAGE process, which is being sponsored by DVC (Research and Commercialisation) Arun Sharma and Registrar, Shard Lorenzo, improving institutional practices including women’s access to career-enhancing opportunities; tackling unconscious bias that might sit behind; and better accommodating career breaks and work-life balance issues.

The issues cover recruitment, pay equity, research-related opportunities, targeted support for promotion and retention; minimising loss of momentum from career breaks; the impact of being non-tenured, and so on.

I’m very pleased that QUT is part of the inaugural group in the national SAGE Athena SWAN process, which will give renewed energy and focus to the area. The QUT gender equity policy and the Athena SWAN principles are a perfect match – they both take a strengths-based approach and talk about the dual need to equip women to navigate the system while at the same time – and more importantly – improving the system itself by removing barriers and biases.

QUT is well on the way in terms of integrating its programs across the university, with some such as the QWIL leadership course being over 20 years old. The more recent programs focussed in the STEMM area seem well-targeted at both women and senior staff, to enable them to use their influence to improve organisational culture.

Part of the SAGE process was a comprehensive survey of STEMM staff. The responses to three open questions are particularly illustrative. Participants were asked to:

• list three things that would assist them to achieve their career goals;

• three things that were obstacles to their career goals; and

• to nominate measures that could improve equity and diversity across QUT.

The responses are striking, particularly when disaggregated for gender. In both actual barriers and potential enablers, one word stood out: time.

Women with all sorts of role profiles talked of being time-poor – doubly so for part-time staff. Women are constrained not only by their caring responsibilities, but also by what they saw as high workloads in their teaching and service roles. Women across the board told us they needed more time to focus on career goals and career enablers.

That’s why I am pleased to see in the draft Action Plan attention to workload allocation, to career breaks, and to improving progression for part-time staff. I’m pleased to see mention of QUT’s ‘relative to opportunity’ policy being applied to all merit assessments. And I’m pleased to see a strategy to hold major meetings only within core hours (9.30am to 4.30pm) – I strongly support this policy and have already enacted it for the Vice-Chancellor’s Advisory Committee.

The second issue which stood out from the survey responses was support.

Women frequently mentioned the desire for mentorship and sponsorship; the importance of support from senior leaders; the need for fair distribution of practical supports such a seed-funding; and how much they appreciated a welcoming organisational culture.

Again, the draft Action Plan works on improving the organisational culture so that it is truly inclusive and supportive, and promotes a rich variety of programs focussed on progression and retention. While senior leaders have a particular responsibility, there’s clearly a role for all staff here.

The way forward is going to require effort across many fronts and for a considerable time. We have challenges all along the length of that leaky pipeline, from schooling to qualification to employment. In STEMM disciplines, we need to recruit more women, and improve their promotion and retention rates, if we want to eliminate the unacceptable gap between genders.

And these imperatives apply not only to women of course, but to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, those living with disabilities, people born overseas (particularly in Asia), and people from a whole host of other under-represented demographics. These imperatives apply especially – especially squared – to women who are also members of these groups.

And we don’t have to wait around for the structural changes to be reformed before taking action. While we implement these programmatic approaches, we can direct steps with both recruitment and ‘growing our own’, targeting those levels in each discipline where the losses are greatest.

We can foster change by finding women at those levels who we can see are really good but who for various reasons have not been able to progress. We can identify these women, support them, mentor them and equip them, clear the path of unfair obstacles, then give them a chance to prove themselves. And we can pull them through. We need to take focused direct action, even while we engage in concerted systemic reform.

We can foster change by harbouring a much broader conversation about the automatic and universal inclusion of women and for all other marginalised people, and by insisting on inclusion riders for speaking events, for committees, for grant application teams, for grant assessment panels, for everything we come together to do.

Because if you don’t know what an inclusion rider is, then check out Frances McDormand’s Academy Award acceptance speech.

With so much other change going on in society, the economy and the sector, the challenge is to maintain momentum and effort over the long haul. And it is a long haul. But we have already come so far that we know we can do it, together. We will be driven by the national focus provided by SAGE, as much as by our own longstanding passion and commitment. I have always been a part of this effort, even before my early leadership roles at Wollongong University many years ago, and I will lead this effort here at QUT.

I look forward to working with each of you, with your colleagues and students, with the women and also the men whom we recruit to this task, because the job is not merely to make this the most gender-equitable university in the country – which we will, mark my words – but much more than that, it is to ensure that it would not even occur to a bright young woman coming into this place that her talent and application and hard work would ever be held back by her gender or her circumstances.

That is our promise to the next generation, it is your promise and mine, and the work we do together to bring it to fruition starts right here, right now.

Thank you.